Agroecology helps feed the world and protect our planet.

There are almost eight billion people who call this planet home. That’s a lot of mouths to feed! Producing enough food for everyone is a complex and challenging process. But the global agricultural industry must continue to evolve if we’re to feed ourselves and safeguard our environments.

To help us explore the growing concept of agroecology, we reached out to Charles Sturt’s PhD candidate Anne Johnson and Professor Geoff Gurr, who are are part of Charles Sturt’s Gulbali Institute.

Chewing over some agricultural facts and figures

Around the world, Anne explains, concerns are increasing about agriculture and its impacts.

- Approximately 40 per cent of the Earth’s land is used for food production and the world’s population is still expanding.

- As a result of some practices, agriculture has become a leading contributor to biodiversity loss.

- Agriculture still relies heavily on chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

“There is widespread acknowledgement that we urgently need to reduce the impact that growing food has on the environment. The status quo of world agriculture, with its reliance on synthetic inputs and ever-expanding areas of cultivation, simply cannot be sustained.”

And that’s where agroecology steps in!

What is agroecology?

Put simply, agroecology uses nature’s services to improve farming practices. Anne explains that agroecology is an alternative system that can bring sustainability to agriculture.

“Agroecology is often discussed in terms of a continuum of improvement. It can start with replacing some practices, but can result in a whole of system redesign based on natural processes.

“It’s not a fixed, prescriptive endpoint; it’s a process where many practices are site-specific. Agroecology is easier to describe when you break it down into three areas.

- Science – that looks at the interactions between the biodiversity in soil, microbes, plants and insects and gives us evidence to combat agriculture problems in new ways.

- Farming – that considers these interactions and uses this biodiversity to improve the way we grow our food without compromising our natural environment.

- Social movement – where farmers collaborate, generating environmental and social outcomes to benefit the whole farming community.

What is agroecology farming?

Well, Anne says it’s about letting nature give us a helping hand!

“A key practice of agroecology is increasing diversity in the farming environment. This can be through diversification of the farm business and also increasing the number of plant species in and around the farm. Biodiverse landscapes are more resilient, especially during adverse events.

“Increasing biodiversity has several ecological health benefits including improvement of soil fertility and organic matter and storage of carbon. For farmers, healthier soils give higher yields and need less inputs. For example:

- Maintaining or planting ground covers means that during heavy rainfall less soil is washed away. That’s good for the farmer and also good for our creeks and rivers.

- Increasing the amount of permanent vegetation, such as tree lines. This can reduce soil erosion and increase the habitat for native birds and animals.

Professor of Applied Ecology, Geoff Gurr explains that agroecology can provide a natural boost, helping farmers dial back artificial inputs.

“Essentially, we can use agroecology to amplify the strength of what ecologists call ecosystem services (aka nature’s contribution to humanity). These are based on processes like beneficial bugs eating pests or microbes breaking down organic matter to release plant nutrients.

“When we harness these ecosystem services it reduces the need for costly and hazardous inputs like pesticides and synthetic fertilisers.”

What are the benefits of agroecology?

Around the world, agroecology has benefited environments, economies and communities. Anne knows it can improve employment, community resilience and mental health – as well as restore biodiversity!

“Agroecology practices contribute to climate change mitigation and improves the health of our soils, plants, people and communities. Agroecology research builds our knowledge of the world and then helps create farming systems that will provide food and rebuild our natural environments.”

“It respects nature and helps make the world an even better place to live. The synergies continuously being discovered in agroecology are exciting. These win-win situations are where the strength of agroecology lies.”

Want some examples? Here are a few research projects that our Charles Sturt applied ecology group have been involved in.

Rice-sesame research project – In Asia, sesame plants were planted around rice fields. It resulted in increasing yields while reducing insecticides – and gave farmers a secondary income. This method has now become an official government recommendation in many regions.

Flowering plants – Students from Tanzania and Ghana collaborated to improve vegetable pest management by using flowering plants to encourage beneficial insects. And in Australia, research by the Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation is helping our vegetable farmers experiment with flowering plants around cabbage fields to suppress pests in a more natural fashion.

Living mulches – In Papua New Guinea, people are looking at ‘living mulches’ to reduce crop losses due to sweet potato weevil.

Human element of agroecology – Anne is currently undertaking a PhD through the Gulbali Institute, exploring how the human element impacts agroecology in viticulture.

The way forward

Anne explains that during the last three decades, the Australian agricultural society industry has evolved.

Early group soil conservation efforts merged into the Landcare era. Initiatives like integrated pest management, conservation agriculture and even regenerative agriculture have become mainstream conversations. Planting tree lines, restoring waterways and improving the efficiency of farming practices have also become common social norms.

“The concept of transitioning to an agroecological mindset from industrial agriculture is not the fringe idea it was a couple of decades ago. Moreover, many of the elements of agroecology are already present in our farming systems – local and international. In 2018, it was estimated that, around the world, nearly 30 per cent of farms had implemented elements of agroecology {Pretty, 2019}.”

So, how will the ag industry continue to progress?

Professor Gurr and the Graham Centre team believe three key elements will help overcome agroecology implementation issues.

- Share, or co-create, knowledge and experience between farmers and researchers. That will mean agroecology practices are site-specific and also practical.

- Demonstrate agroecology success in practical, economic and social terms. Think site-specific research or engineering developments.

- Develop a guide for farmers. One that has practical, small steps they can take.

But, Professor Gurr notes, change must come at an acceptable pace.

“In the last 20 years we’ve conducted a lot of research at our Orange campus. It appears that the key to greater agroecology adoption is to develop small steps that farmers can take. We need a paradigm nudge rather than a paradigm shift!

“For example, agroecology research can help identify just the right type of biodiversity that a farmer can incorporate. All while having minimal disruption to their normal agronomic practices.”

You can make a difference

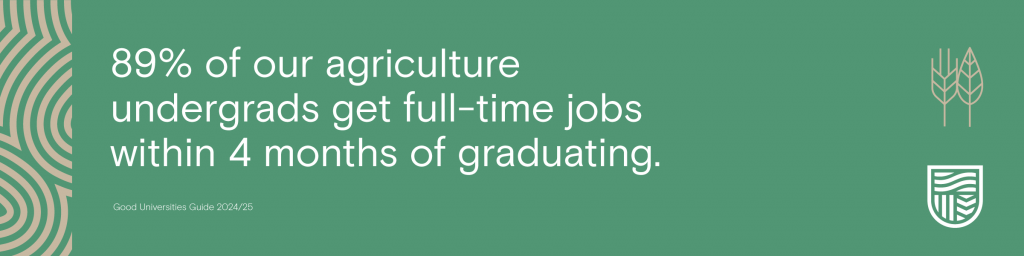

Agriculture is an increasingly complex and sophisticated industry. And it’s one that has a vital role in our sustainable future. Play your part with an agricultural degree from Charles Sturt University. From undergraduate courses to research degrees, however you want to make a difference, you can here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.