The impact of drought upon industries, jobs, communities and the environment is immense. Especially given drought is a recurring issue that has few workable solutions. Current thinking is to try and better manage the dwindling water resources we have. But when it comes to surviving times of drought in Australia, is new water generation the answer? Charles Sturt University’s Emeritus Professor Jim Pratley thinks so.

Crippling impact of drought

Dry rivers, bare paddocks, fewer livestock, reduced production and job losses. As a research professor in agriculture and member of Charles Sturt University’s Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation, Professor Pratley knows drought is an insidious beast.

“You just have to look at the loss of gross value of production (GVP) in NSW to determine that the impact of drought is enormous. Since 2000, we’ve lost around $50 billion. The GVP in NSW drops by half when we experience a significant drought. And we’ve had nine significant drought years since 2000!

“Latest reports indicate that 2019 will be the new normal in terms of weather patterns. Now, 2019 was a disaster for south-east Australia. If that’s the new normal – we ain’t going to survive!

“Our industries will disappear. They can’t operate for only one year out of three or four. And we had communities that ran out of water in 2019. Guyra, Tamworth, Menindee, Bourke, Armidale.

“So, doing what we’ve always done in terms of shoring up our water supply will not solve the problem.”

The way it is (which isn’t working)

Professor Pratley knows that trying to preserve what limited water we have and making it stretch further is not a long-term solution for a country like Australia.

“We have a water supply generated by rainfall and we’re totally dependent upon that. The reality is, that water source doesn’t satisfy the needs of the community, industry or the environment. We spend a lot of time trying to manipulate how we manage that water – trying to deliver better outcomes. But there just isn’t enough water.

“Moving forward, the only way I can see to sustain our inland communities, in particular, is to introduce new sources of water.”

What is new water?

To generate new water the Professor is revisiting and building on some old thinking, because new water includes:

- recycling existing supplies

- desalinating sea water.

A little irony and some desalinated water

The irony, the Professor says, is that while Australia is the driest inhabited continent in the world, we’re surrounded by unlimited amounts of water!

“It’s salty water and it’s a long way from where we need to use it, but if we’re really serious about sustaining our environment then we have to introduce new sources of water into our natural systems and that includes desalinated water.

“Let’s look at pipelining that around Australia. Interestingly, we can pipeline gas and a fibre network – no trouble at all. But when it comes to putting a water pipeline around Australia, well, that seems really difficult to do. I don’t understand why.

“We already have a desalination pipeline that goes from the Gold Coast to Toowoomba. We have desalination plants all around the coast, but most of them lay idle. Well, it’s about time coastal locations fired up the desal plants and stopped taking water from inland.

“The pipeline that goes over the mountains to the Oberon Dam takes water from there into the coastal system. A pipeline takes water from the Goulburn River system to the Melbourne water supply. And there are at least two pipelines from the Murray River into Adelaide. We need to be shipping all this water the other way – from the coast back into our inland dams and rivers.”

Knocking down the cost barriers

Aside from the pipeline issue, desalination has never really got to the starting line due to the energy costs associated with running the plants. It’s time to rethink that barrier as well, according to the professor.

“As well as the costs of building and maintaining the pipelines, traditional energy costs of desalination are pretty high. They come in around 50–60 per cent of the total costs. But these days, surely, we should be using renewable energy to power our desalination plants. Defray the costs of energy. Especially since people around the world are talking about halving the cost of desalination by 2030.

“Israel has done it and now supply fresh water to neighbouring middle eastern countries. And their water supply was effectively zilch before desalination. They are the blueprint for what needs to be done.”

Recycle, recycle, recycle

Reduce, reuse and recycle. The Professor says it’s a mantra that we need to adopt if we are serious about water sustainability.

“We seem to think we should only use water once. Australia’s one of only a few countries in the world that does that. Most just recycle and recycle and recycle.

“Sydney Water has a regulation whereby they can only, more or less, use their water once before they have to dump it out to sea or into our rivers. I’ve done a calculation that shows if the Sydney supply was at capacity, they’d have a four-year supply. But if we recycled 80 per cent of it, they’d have a 20-year water supply!

“It’s ridiculous to the extreme to dump the water into a river like the Hawkesbury, as it has to be treated to potable levels. That’s exactly what we have to do to recycle it! So, just by a stroke of the pen we could change the system and have access to greater levels of water.

“Let’s dive into it a little more and again use the Hawkesbury as an example. Communities at the top of the river take water out, use it, treat it and put it back into the river. So, communities downstream take water out of the river which is part fresh, part treated. They use that water, retreat it and dump it back into the system.

“That means a significant part of Sydney already operates on a recycled system. It’s such a simple issue that could transform Sydney water. And if we did that, then they’ll stop taking water from an already drought-affected inland.”

The ‘yuk’ factor

If other countries are recycling their water as a matter of course, why aren’t we? Professor Pratley explains the somewhat unscientific barrier to Australia becoming a nation which recycles water on a very large scale.

“In this country we are way out of touch when it comes to water recycling. Australians are very precious in many ways and using water only once is an example.

“We have the ‘yuk’ factor. Not wanting to use recycled water that has come from sewage, gutters or the like.

“But the treatment of water is pretty sophisticated these days. It’s actually very difficult to tell treated water from fresh water. If the technology is good enough, then there isn’t a risk.

“In a country like ours we can’t afford to adopt the ‘yuk’ factor because we just don’t have enough water. We need governments to be politically courageous, acknowledge that enough is enough and begin to recycle 80 per cent of our water.”

A dangerous mirage

When the rains finally arrive, and paddocks turn green and dams fill up, Professor Pratley believes we begin to see a dangerous mirage.

“Communities have now softened towards water availability. During the drought we really should have acknowledged that we needed change, needed to recycle our water. But now our water systems have filled up and we tend to not think about it too much.

“On top of that, the Sydney water regulators have also reduced restrictions. That’s ridiculous. We should be keeping those low-level restrictions, like not hosing down driveways or washing cars on the road. It should be normal practice to water your garden in the cool parts of the day.

“Let’s save water when we’ve got plenty. Then it will last longer during times of drought. Let’s put a value on water that makes people think a little about whether they leave the tap running.”

You can make a difference

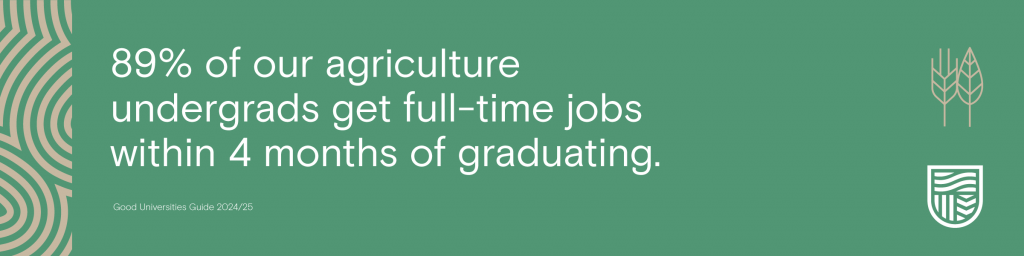

Agriculture is an increasingly complex and sophisticated industry – one that will play a vital role in our sustainable future. Play your part with an agricultural degree from Charles Sturt University. From undergraduate courses to research degrees, however you want to make a difference, you can here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.