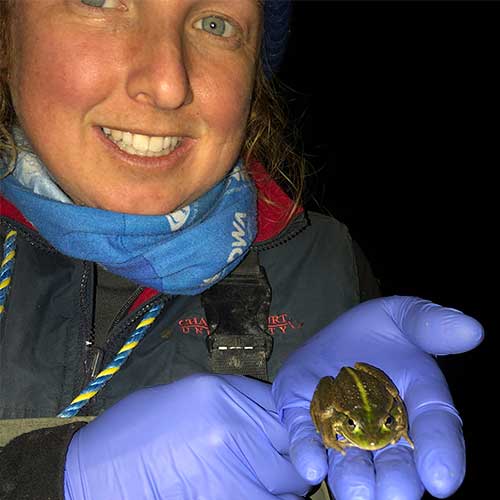

How important is a frog to its environment? What about an entire species? What would it say about us as a society if we didn’t endeavour to preserve endangered species? How can we ensure the best outcomes for animals, plants, natural ecosystems… and people? These are the types of questions that Professor Skye Wassens, an ecologist based at Charles Sturt University’s Albury-Wodonga campus, is asking in her endangered species research.

Professor Wassens leads the Murrumbidgee Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Program at Charles Sturt University. This project seeks to understand the complex relationships between water management and the survival of water dependant plants and animals. The aim is to protect the region’s unique environment and wildlife areas, while balancing support of critical agricultural and human needs. That means native plants and animals. Animals like the southern bell frog.

Understanding the needs of endangered species

Professor Wassens’ endangered animals research project informs crucial decisions about how the water we have available is used.

“The project has been running in various forms for around 20 years. Our research directly feeds into decisions on how to best manage environmental water allocations to support southern bell frog populations. Our research supports water managers who must prioritise environmental water flows to meet the requirements of a wide range of species. For southern bell frogs, that means ensuring watering replicates as much as possible the natural long-duration spring that supports breeding, as well as preserving more permanent bodies of water that support adult frogs through dry times.

“Weather patterns also influence decision-making. For instance, in very dry years, we focus on maintaining refuges, just to keep the population going. That’s instead of encouraging population growth – as we just won’t have the water available to support that. If we have more water available, we can then look at promoting a breeding event.

“Bell frogs need water year round. To breed, however, they need large areas of recently inundated habitat. That means shallow temporary floodplains in which to lay their eggs and the tadpoles develop. We have a high level of water extraction and management in our river systems. We’ve lost the natural flooding and inundation regime that these frogs evolved with. There is no longer the natural water cycle that would support sufficient breeding for species survival. So the management of the frog populations has to be an ongoing project to prevent it becoming an endangered species.

“Essentially, in these highly managed systems, we have to decide when and how to create the environments that the frogs need to survive.”

Managing multiple demands

The water management systems that Professor Wassens’ endangered species research contributes to don’t just focus on wildlife. There are a whole range of demands on the water that need to be navigated.

“The water flow in many of our rivers is regulated by large headwater dams, weirs and diversion structures. The water in the dams is shared between different users, who own a water entitlement, which is a right to a share of the water within the river. This includes irrigators and industry. The environment effectively owns a water entitlement through the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder and various state agencies. In effect, every drop of water in the rivers is owned by someone, and it has to be divvied up. It’s a challenging situation.

“The catchment area supports a productive agricultural community, has a rich and diverse First Nations history, and supports recreational uses, such as fishing, bird-watching and bushwalking. Many Aboriginal nations maintain strong connections to the country served by the river system. These include the Wiradjuri, Nari-Nari, Mudi-Mudi, and the Waddi Waddi. And the Toogimbe Indigenous Protected Area is an important area of cultural and environmental heritage managed by the Nari-Nari Tribal Council.

“Actually moving the water is relatively easy, as we have that infrastructure in place. However, with so many demands on it, getting sufficient water for all these elements can be hard.

“There are rules around water allocation. Not just to protect the environment, but also to prevent communities running out of water and companies taking too much. But the policy arena can change. And of course, when there is a drought and water is even scarcer, arguments for more resources can intensify.”

Taking a holistic approach to endangered species research

Complex interactions are exactly what Professor Wassens and her team are tackling – getting their feet wet (literally) to develop a more comprehensive understanding.

“The effective management of these river and floodplain systems is not just important for the frogs – although they are a crucial species within that ecosystem. It’s also important for many endangered animals. Species that make their home in this river system include the trout cod, Murray cod, silver perch and Macquarie perch. Turtle species and the fishing bat are also vulnerable. The Lowbidgee floodplain also contains some of the Murray-Darling Basin’s largest breeding sites for nesting water birds. Not to mention all the native plants that rely on the water the river system provides for survival.

“So when we’re conducting this endangered animals research project, we look at the whole ecosystem, alongside the frog life cycle. We also have a PhD student looking at disease in the frogs. And we liaise with other teams looking at things like the actions and prevalence of parasites in aquatic ecosystems. Having a rich picture of the whole biodiverse system makes it much easier to react to changing situations.”

Climate change, drought and frog numbers

These situations are increasingly related to drought.

“Before the Millennium Drought the southern bell frog, while in severe decline across Australia, was considered to be secure in the lower Murrumbidgee. But that drought really hit the population hard. It’s only in the last few years that we’re seeing sustained increases and near pre-Millennium Drought levels.”

However, recent dry conditions are putting the southern bell frog at risk once again.

“In times when water is more plentiful, we manage the water systems to try and boost breeding events. Consequently, this gives us larger population numbers to ‘see out’ drier years when breeding inevitably reduces. But that can only see through one, maybe two years of drought. If we have four or five years of sustained drought, that’s going to significantly affect numbers.

“High temperatures also mean high evaporation rates. In addition, that further depletes water levels – and, of course, means we don’t have the water available to divert to compensate for that evaporation. Even wildfires could potentially have an impact on numbers, as there is little refuge from them if floodplains and river systems have low levels of water.

“In the absence of climate change we would be confident of the ongoing survival of the southern bell frog. Over the years we have developed good water management systems to ensure this. However, with climate change, that management becomes so much harder, and so does preserving the frogs.

“As a society we have made the decision to try to prevent further extinction of native plants and animals. Most importantly, once you’ve lost these species, that’s it, and it only takes a couple of years of drought to decimate their numbers.”

Do you want to help save our endangered species?

There’s never been a more important time to focus on our wild environments and endangered species. They are under pressure like never before, not least through climate change. Getting hands-on experience as you learn is key to making a difference. So whether you are just starting out in environmental management, progressing your knowledge of wildlife, or keen to follow Professor Wassens’ example and move into endangered species research, at Charles Sturt University you can. Let’s get to work.

You must be logged in to post a comment.