There’s a lot of noise being made today on behalf of threatened species in Australia. But what happens if your voice isn’t being heard? Who’s fighting for the underdogs of the animal kingdom? Well, it just so happens that the city of Albury, in regional New South Wales, is home to both an underdog (turtle) and its human champion (an American in Oz).

James Van Dyke, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer in Biomedical Sciences with La Trobe University who headed Down Under in 2012 after being awarded a National Science Foundation International Research Fellowship. He spent five years working with universities in Sydney before joining Charles Sturt University in 2017 – where he spent almost two years continuing his valuable work on turtle conservation.

Dr Van Dyke explains that not many people are fond of snakes and some aren’t fussed with lizards – but the turtle seems to have the charismatic underdog factor in its favour. Unfortunately, it’s not on a scale big enough to put their plight firmly in the global spotlight. They just don’t make the big league like pandas, whales or polar bears who command the world’s attention and empathy. Nor are they koalas, wombats or platypi who have also captured the interest of Australians.

The humble turtle seems to remain under the radar – and under threat. Cue Threatened Species Day, which is held around the globe on 7 September each year.

“When you look at all the species of turtles, more than 60 per cent of them are listed as threatened, endangered, vulnerable or extinct – depending on where in the world you go. Surprisingly, they are one of the most endangered vertebrate groups – to my knowledge, the only ones who come close are primates and cats. They’re in pretty bad shape.”

Turtles face threats on all fronts

So, Dr Van Dyke believes, now is the perfect time to raise awareness of the turtle’s predicament given they are battling threats on a variety of fronts. Humans, climate change, predators.

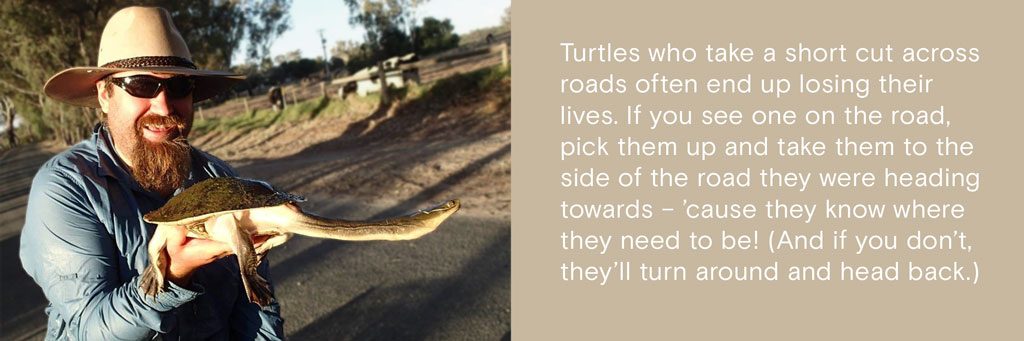

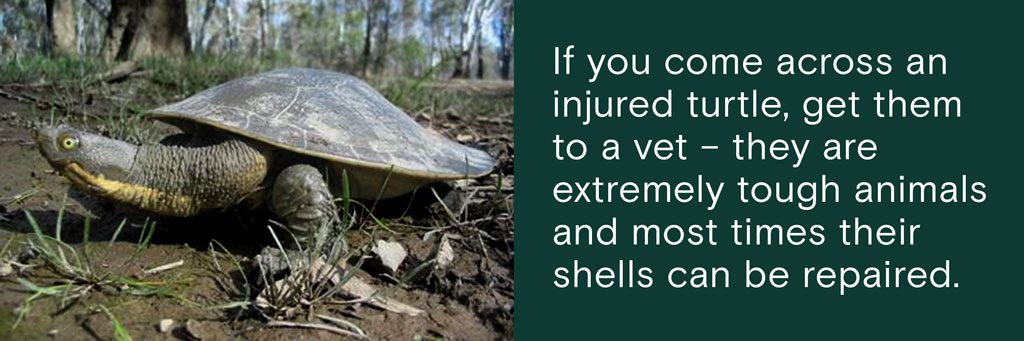

“In a number of areas across the world turtles are still a big food source. [Turtle soup is still a popular dish.] Sea turtles get caught in fishing nets and turtles who live on land or in freshwater cross roads and get hit. Then there’s habitat loss which, for freshwater species in particular, is a major threat. In Australia we’ve had changes to water regimes with irrigation and human water use – we’ve lost a lot of our historic wetlands. And that is habitat that is just gone for a species which used to rely on it.

“Another climate change issue is the change in rainfall. We don’t know what happens to the turtles when a river dries up, as apparently some parts of the Murray-Darling have done. And another concern I have is rising temperatures. Earlier this year, after the February heatwave, a student went to check nesting turtles … and unfortunately what they found was the babies had cooked inside the nest. We don’t yet know how big an issue this is.”

But perhaps the most immediate threat to the turtle’s future, especially along the Murray River, is the red fox.

“In places like Australia – including in Albury – invasive predators like the red fox really, really hammer the eggs.”

More than meets the eye: the perception of persistence

Charles Sturt’s Albury-Wodonga campus sits near Australia’s longest river, the Murray. Running for more than 2,500 kilometres and reaching across three states (New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia) it is the lifeblood of many human and animal communities. But the mighty Murray is also providing researchers like Dr Van Dyke with some stark warnings.

“We have done surveys all up and down the Murray River and in most of the tributaries, and if we go down stream to South Australia, the turtle numbers get lower and lower. If you talk to the residents of the area, including the traditional owners, they will tell you they just don’t see turtles in numbers like they used to.

“What we have seen is a kind of ‘crash’ happen in South Australia. And it was predicted back in the early 1980s by some of the folks who I now work with.

“They were seeing large numbers of nests being destroyed by foxes and when they were doing trapping surveys they weren’t catching juveniles.

Dr James Van Dyke

“The nest destruction by foxes was removing the source of baby turtles from the environment. If there’s no hatchlings or juveniles coming into the system, then as the mature turtles start to die from old age, the population can disappear relatively quickly.”

Basically, it might look healthy for a long time – you’ll see lots of adult turtles – but then one day they just won’t be there – and there will be none coming up through the ranks.

“In research literature this has been called the perception of persistence. Because we’re seeing them all the time we assume that they’re fine and don’t need help. But that is a false sense of security.”

Threatened species in our own backyard

Dr Van Dyke explains that Albury still has relatively large numbers of adult turtles but these numbers don’t necessarily assure a prosperous future.

“In spring or autumn down by the shore or in a log-out, you are likely to see them basking in the sun. And people will say ‘we see them all the time and they don’t look like they’re in trouble’. But in terms of our surveys, what we are seeing in Albury now mirrors the scenario seen in South Australia in the 1980s – that pattern of high nest destruction, but lots of adult turtles. We are not seeing hatchlings, juveniles or sub-adults in the system.”

The good news?

“In Albury, we still have one or two decades to rectify the situation and address the South Australian pattern.

Dr James Van Dyke

“As far as we know, turtles don’t have a menopause. They continue to reproduce until they die. So, the females who are still out there will reproduce every year. My guess is that these turtles have a lifespan of 50 to 100 years. If they mature at 10 years, then they’ve got potentially at least 40 years to reproduce, with a nest each year. And with 20 eggs per clutch that is 800 eggs that a single turtle might lay in her lifetime.”

Addressing the fox threat may take the nest mortality rate from 95-100 per cent to a slightly less horrifying 70 per cent. And these survivors would still have to contend with other predators including quolls, goannas, and dingoes.

“But if a whole nest survives to hatching and those babies make it to the water, then their survival rate improves because they can hide better in the water. Though they’ll still have to battle egrets and herons, Murray cod and water rats.”

Out foxing the threat

The key is to find ways to protect those nests from foxes. But here’s the challenge.

“Though there are other threats, we think that if we can handle the foxes then at least we can get some babies into the population. But we haven’t had much success with traditional methods of fox control like shooting or poison baiting. It just doesn’t kill enough foxes. For lethal controls to work in terms of foxes we need to have total eradication – and that’s a lot harder to achieve than people realise. Clear out an area’s fox population and others will move into the habitant from places where you haven’t been able to effectively control their numbers.

“Cameras on some of our nesting plots have captured a single fox taking out 15 nests in one night.

“So, even if we bait nine out of 10 foxes in one area, the remaining fox can still do as much damage as the whole 10 would have done anyway.”

Dr James Van Dyke

A change of tack is called for, and new methods of conservation are being explored.

“We are now looking at alternative methods, such as working with community groups to locate nests and then we predict times during the year when they’ll be actively nesting. Then it’s a matter of going out and looking for them. If you find a turtle in the process of nesting, wait. Then when she’s finished, cover the nest with mesh to basically protect it from foxes. The mesh is still big enough for the babies to dig out of and make their way to the water.”

Hatching a plan

Dr Van Dyke is also currently working with a range of partners to develop a program called head starting.

“Basically, if we can’t keep the foxes from the eggs we are going to try and remove the eggs from the foxes. Community group involvement is one way of doing that. We are determining whether we can harvest the eggs from the females as they’re nesting and, instead of letting them incubate naturally, bring them into captivity. Then, once they hatch, we release the babies.

“Here in the Upper Murray we are seeing the warning signs for threatened species, but we still have turtles. As long as they’re here we have possibilities – there’s things we can do. If the entire Murray River looked like South Australia the picture would be much worse because we’d have no turtles to work with.”

More good news for this threatened species

In his adjunct role with Charles Sturt, Dr James co-supervises students and maintains access to the Albury-Wodonga campus’ ecologically significant wetlands – where he spent considerable time researching the turtle population.

“We trapped more than 100 different eastern long-neck turtles in the wetlands. It’s a pretty good population – and there are still some juveniles. Turtles seem to be doing better in the Charles Sturt wetlands than a lot of other places I’ve been. So, one of the continuing questions is ‘why don’t they seem to experience the nest mortality rate from foxes?’

“The wetlands is an interesting place that’s a little different and if we can figure out what makes it different maybe we can apply it elsewhere.”

Dr James Van Dyke

Let’s hope so, for the sake of Albury’s cutest underdog – the turtle.

Creating a world worth living in

What does a better world look like to you? Does it mean finding a cure for illnesses, improving education, making new discoveries, developing innovative technologies or helping to protect a threatened species in Australia?

Our wide range of courses will give you the skills and industry knowledge so you can be the change you want to see in the world. Follow your heart, get qualified and land a job you’ll love with Charles Sturt University. Let’s get to work!

You must be logged in to post a comment.